Tom Georgiev shot me. Not literally, of course, yet, with a weapon as formidable as any gun: his camera. He was asked by The Sunday Times to take my portrait for an article about narcissism, one of my fields of interest.

The photographer's worst enemy is his ego. A good photographer needs to learn to step aside, fade, as it were, and let the confluences of imagery and circumstance do the talking through his lens. It, therefore, impressed me that Tom was willing - eager, even - to suspend his preconceptions and consider some of my ideas for locations and staging.

Tom was wide open to me, as his subject, and to the world. Throughout our session, with amazing panache and lightning speed, he incorporated into his work elements from kaleidoscopic street scenes: overpasses, railway stations, cars, peeling posters, glazed windowpanes, rickety, abandoned furniture, and even a donkey made it into his photos. He captured the essence of all these objects - their uniqueness - as well as their interconnectedness. He leveraged these instant, serendipitous, and fortuitous assets and molded them into artifacts and art pieces.

Indeed, this is Tom's forte: his ability to use angles, designs, height differentials, gradients - the shifting geometries offered by his (mostly urban) locales - to highlight and point out the quiddity of his topic and subject matter. By combining the mundane (e.g., objects such as bicycles) with the abstract, the human with the mechanic, the emotive with the geometrical, Tom succeeds to convey irony without malice, insight devoid of cynicism, sad love without bathos. He is a poet that knowingly subjects himself to the rigorous discipline of the scientist.

Confronted with Tom's photos, I am always left breathless by their implied audacity and deep penetration. "How haven't I noticed this before?" - I gasp - "This is so obvious!". Or: "This is so true ... and, yet ... impossible!". Tom's work suggests occult undercurrents that bind Man, his environment (both natural and artificial), his inner landscape, and Others. His oeuvre is never surrealistic, fantastic, or naive - but always magical, an enchanted commentary, an annotated introduction to the ineluctable absurdity of our existence.

Still, all these attributes would have been of little use without Tom's incredible sense of timing. Tom resonates with the dynamics of man-made events, with the flow of traffic, with the shimmering air, with the flickering of reflections. He is enamored with motion and with what it reveals about the inner nature of the world around him. His relationship with time itself is intimate: he freezes, sniffing it, and then, like a well-honed predator, he traps the moment with his clucking shutter, triumphantly displaying his spoils, framed and vibrant.

Tom is arguably the best-known press photographer in Macedonia. With his ubiquitous camera, he is responsible for many by now iconic images. Inevitably, his oft-awarded work, aided and abetted by that great leveler of fields, the Internet, is now becoming known throughout the world. He continues the proud tradition of photojournalists who were and are also perceptive and prodigious artists. Equally fluent in color and in black and white, he transforms reality into art with well-timed and well-chosen clicks of his apparatus.

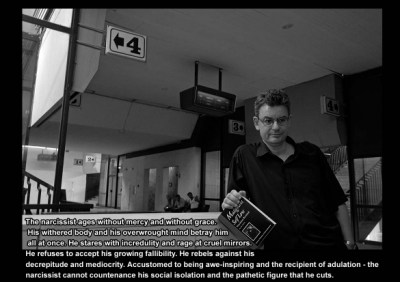

The Narcissist Grows Old

The narcissist ages without mercy and without grace. His withered body and his overwrought mind betray him all at once. He stares with incredulity and rage at cruel mirrors. He refuses to accept his growing fallibility. He rebels against his decrepitude and mediocrity. Accustomed to being awe-inspiring and the recipient of adulation - the narcissist cannot countenance his social isolation and the pathetic figure that he cuts.